Since my father died on this day a year ago, I have often revisited in my mind, or in my imagination, the last moments of his life. What they were like. What he felt, what he knew. What he heard and smelled. Did his life flash before him on a reel, the hills of Tuscany, the words of his mother, the laughter of his children. Music. Love. Did his heart ache?

I was on the opposite coast of the United States when he exhaled his last breath — the word I so like in Italian, spirare — but I know that he had been sleeping peacefully after a fitful night. And then, at the turn of the head he left. He went off somewhere.

Where did he go, I wonder often sitting in the bathtub, running hot water over my flesh, so finite. Where do we go?

The act or fact or reality of my dad’s last breath, the thought of it, irretrievable, absolute, irrecoverable, irrevocable, the mere thought of it, the words themselves, cause me infinite ache right in the hollow on my chest. Lost to the wind, that last exhale cannot be caught and put back, like I’d like to do with the hands of a child, stuffing the air back into his mouth with little fingers and then covering it, laughing, telling him to not let it out again, and him holding his breath laughing the way we used to do, his dark eyes playful above my grasping hands. Breathe it back in, Dad, I say! Breathe! Come back! Come back!

But no, it is not so: That final flame of energy glowing in his heart till the very final instant of life went out like a single last piece of coal left burning in a fireplace after the rest of the house has turned off the lights and gone to sleep. So it is with the heart, the last keeper of us.

And that was it. He left.

Since that day a year ago I have often tried to recast that image, a suffering one in the end because I know that my dad, I am confident, was acutely aware of dying and I think that before that peaceful final sleep he had wrestled with death hand to hand over two anguished and restless nights, and that image, that thought, hurts me, it hurts me to the bone, that suffering that I know he felt, and I push it away and push it away, and so in the process of recasting it I have come to a memory, an image of my father that I have always held dear.

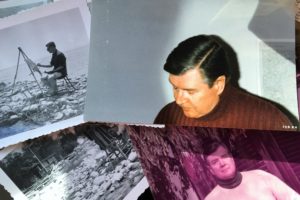

When I was little, well, all throughout our lives in Cetona, sometimes in the afternoon Dad would put down his tools, take off his white lab coat, and go upstairs to take a very short nap. On the upper floors our house didn’t have any doors (the Miesian idea of privacy) — all the bedrooms, each on a different floor, landed straight off a spiral staircase — and if I walked up to my room through my parents’ bedroom tiptoeing on the steps to not wake him, I would see Dad asleep on the bed in the position he always napped in: fully dressed, on his back, hands resting on his chest, fingers intertwined, ankles neatly crossed, thin black socks, always black, face upward and at rest, head a bit tilted to the left, thick black hair slicked back, and his chest rising ever so slightly.

It never varied, really, from my young childhood through my early twenties, from when I was downstairs playing with dolls to when I was downstairs studying for tests in high school, and there was something comforting and reassuring and tender in this, my dad resting just so, and me tiptoeing on the wooden steps to not wake him and to watch over him. And today, today and all days when I wonder about that last breath, that’s where I picture him, in his faded jeans and favorite terracotta-colored turtleneck, looking forward in his sleep, at peace on the brightly colored bedspread, the bustle of the house quieted for him and the countryside peaceful outside.

That’s the way I like to imagine it all. Quiet sleep cradling him, forever.

Rest well, Daddy. Missing you every day.