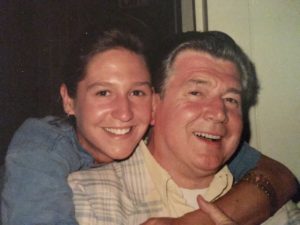

Today at sundown I buried the remains of our father in an olive grove looking out onto Cetona.

I chose the place because I thought he would have liked to look out here, across the way to our old house and the town he so loved. It is the place he brought me as a child, and my brother, and my mother, our family, to be with him in the pursuit of his passions and sensibilities.

I have read in his notes, recently, since he died, about what moved him about architecture and building and music and landscape, and it makes sense thoroughly and deeply that part of him be here in this place where all of that came together into a single strand of his being.

Where materials and proportions, color and texture merge to form what he thought to be utter perfection to be lived individually and socially with much care.

Before our father died we talked at length as a family about what he wanted done of him. When we asked about the scattering or burying of his ashes he was puzzled as if it absolutely made no sense to him. He would be gone, he said. It did not matter.

And yet … it mattered to me, to all of us, and I think, in the end, to him, too.

Since he died in Eugene, Oregon, as a family we decided that part of him—the chapter of his second family and third child—would remain in the States, on the West Coast, maybe in the Pacific Ocean that he visited so happily. And so that is.

For our part, I transported the ashes of our father to Charleston, and now, here, to Cetona, where my brother Paul and I thought his other part should be.

It’s not about dividing a corpse; it’s about the observance of death reflecting the life and loves and passions one has lived, and our father certainly had many.

I like to think that he would approve of this, this very special place I chose for him, an olive grove—symbol of peace and unity—belonging to a dear friend where one day I also hope to rest. It sits almost exactly at the height of Gert’s house, Dad, and from here you can look down and to the right almost to our old house.

Behind and above you sits Monte Cetona, looking over you at night with its tiny solitary lights and its quiet, comforting presence. At sunrise and sunset, the light in this olive grove is pastel and soft and soothing, as you knew it, and at midday you rest sheltered in the shade of an olive tree, just feet away from a glorious fig tree you would like, whose handlike leaves you would like to draw. Before you are the arches and doorways and terraces and porticos and towers—the harmony—you so admired, and around you people will till and live in the landscape you so loved.

In leaving you there today I sat in the grasses beneath the olive trees and ran your ashes through my hands, Dad. I felt your thick black hair run through my fingers, your nails with the ridges I have, from Grandma; your hands so handsome, your intense brown eyes, your footsteps, your heartbeat, your brain, so alive. I held you in my palm, the gravel of the bones that supported you, your broad jaw, the bump in your nose, which all of us children of yours took from you, and your teeth, framed in your smile always full when honestly happy and not so much when not.

As I let your ashes fall under the olive tree I imagined your cheekbones rising in laughter, your head tilting back in happiness and marvel, and your spirit rising above and looking out.

Today, Dad, you are here, across the way from the place you chose to be at one time, and the place you chose for me, for us, and here I will visit you again, for sure, always.

Godspeed, Dad. May you have a good martini with Leonardo, shaken, dirty, with onions, as you liked it.

Always with love.