The time came after my father’s death a few months ago to go through his things, to sort through the belongings that made up the remnants of his life, to decide what to do with it all.

I set out to identify things that I cared to keep, and also to find things of my father’s that could be preserved and used for a posthumous and greater purpose—to give my father continuity, which my father did not believe could be obtained by the simple act of procreation.

I spent a week in Oregon going through boxes, a meandering voyage that quickly ceased being about a division of goods or a daughter’s search for the nostalgic memento and turned rather into an appreciation and a minding of the life of my father, the man David Fix.

It was not a simple, narrow, or easily quantified path: His life had periods, like the life of a painter, and, within them, phases and side streets, too. During the course of my very early childhood, my father had been an architect, in Chicago, where I was born, working for Mies van der Rohe. Then, after we moved to Italy, he had become a violinmaker, the profession he performed and breathed during the course of the rest of my childhood and my adolescence, up to my mid-twenties. It was what my dad did for most of the years I spent in his company, a calling he embarked on in his late thirties and whose learning and challenges and joys had colored most of my own life.

Then, after my college and grad school, my father and mother parted and my father went on to have a second family and also a second career, that as a university professor in architecture, at the University of Miami, back in the States. He was lucky to be able to move from one life to another so fruitfully, but of course I lived much of it from a distance. I visited my father and his new family many times in Miami, and I attended some classes that Dad taught at UM, where, I learned, he became a beloved professor.

Wrapping up such a life is no small thing. It entails going through dozens and dozens of boxes, each a chapter of a lifetime, a prolific output of a complex, talented, creative, and fertile mind. The process broke me and took me in a million directions, sad and heavy and grievous.

Yet, it also granted me a singular awakening, taking me from David the father to David the man and gifting me an experience and a light I would not have otherwise had.

In my perusing of my father’s things from the Cremona period, I found boxes of his violinmaking tools, pialle and sgorbie and all sorts of things large and small whose names I do not know in English or Italian but whose images color my memories, lined up orderly as they were on the thick slab of his banco in his lab. I found his early violin schematics and the binders in which he took meticulous notes when he was a student learning his new craft, detailing the construction of an instrument in every detail from start to finish.

I found parts of a violin in the making—the fondo, or bottom, and the top, and the fascie, those fine sinuous strips that make up the sides of a violin. The neck is missing, and the scroll, too. My father carried or shipped that violin from Italy to the States when he left and he kept it under wraps so tightly for twenty-five years that it had holes from termites. That illustrates how much he cared about and still cherished the work he had done, and perhaps he harbored a dream of returning to it once again someday. Surely that period of his life represented something worth carrying around for a very long time, and for that reason I have asked a violinmaking colleague of Dad’s back from their time together in Cremona—also named David—to put it together for me, for us, as a keepsake.

From Dad’s early architectural career I found many of his drawings, from many projects dating years back, and his architectural templates, the little plastic templates architects used—when they still drew by hand—to draw a standard shower or a kitchen counter, or, most importantly, the tiny bathtub in which in every new building Dad always placed me in the form of a little stick figure.

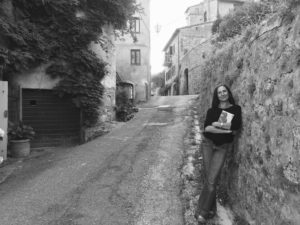

I found and sent home to myself a set of my father’s compasses, some rulers, an X-Acto knife, some ink pens, a drafting brush, a ruler and a measuring stick that sat on his work bench in Cetona for twenty years. I found the original drawings of the restoration of our house in Cetona, and drawings of work he had done for others—of fireplaces (it was a pet-peeve of Dad’s that few seemed able to draw and build a fireplace that draws properly), and drawings of chairs he had done in the 1960s on Mies van der Rohe stationery in Chicago.

I found an envelope of the things he used to draw for me sitting at the kitchen table after lunch—sketches of random things that occupied our daily conversations, such as trees or landscape or geometry—and also things he hung on the walls of his studio, including clips of beautiful women placed in the context of design: a breast with a geometrical meaning, a model with Dad’s Golden Ratio lines juxtaposed, and then even sketches of a vulva with pictorial analysis, something related comically to geometry.

Of course, my father would have objected to me touching any of this. I can imagine his stern look under arched eyebrows, dark eyes disapproving of my invasion and disruption of his order. He hated his things being touched or moved.

But then, Dad, I would have nothing of this to tell, and so many holes unfilled.

In Dad’s boxes I found also his famous violin varnish studies, a side street he took at some point in his violinmaking career. Everyone in my family groans at the mere sound of the words “violin varnish” because this particular enterprise—the study of the relationship between varnish and sound, one of those unsolvable mental meanderings that drives one to insanity—took my father far afield from his making of instruments and ultimately contributed to driving our family to ruin, financially and emotionally. It was a moat my dad could not drag himself from.

But, of course, after it was all said and done, after leaving Cetona my father rebounded mentally and emotionally and at the age of sixty or better he went on to have a productive and successful life as an architecture professor. He was a natural teacher, my father, and this chapter in his life was rewarding and well deserved. Over twenty years his courses encompassed things his mind was naturally lent to and that he had contemplated deeply throughout his life in different settings: wind and ventilation, and windows and doors, light, the structure of walls, the sustainability of building and of course, arches, by which my father was entranced as the marvel of design and mathematical principle that they are. I remember my father drawing arches for me as a little girl, on little scraps of paper, with his ink pens, detailing the chiave di volta that holds them together just so.

After a few years at UM Dad became part of the Rome program, taking graduate architecture students to study ancient Rome. Over the years he became the professor of the program, though he insisted humbly that he would never be able to master the understanding of this city whose layers peeled magically like the skins of onions. He, as usual, delved into this with the full passion of his mind and heart: He developed maps of the historical layers as they moved through the different parts of the ancient city and researched and wrote a chronology of Rome that is staple to the Rome program at UM today. I reviewed and looked at his every syllabus and notes, and everything is well beyond anything that I can take in. Every year he took students to Rome, sometimes twice a year, and he never stopped inquiring and wondering what was below and beneath the story of Rome that he had not yet understood or mastered, right up to the point where he could barely walk anymore. And that was the beginning of his end. He retired from UM in 2015 at 83.

In the boxes covering his most recent years, up to right before he died, were hundreds of pages of notes about architecture and its greater meaning: About what makes a good architect, and a good building, and what he considered the ethical code of an architect. In his notes, much to be explored still, I find, I think, an explanation of why my father never really wanted to practice architecture, in spite—and specifically because of—his ethics and integrity as an architect. There is no such thing as “practicing architecture,” he wrote on one piece of paper. He was deeply cognizant of the impact of buildings on the earth and on public life, and he could not shake that importance. He could not indulge the idea of the individual ego shaping so drastically the life and future of others.

When he died he was writing an article (a book?) about Mies, having to do with something my father had understood about the essence of his mentor, something that, regretfully, I will never be able to convey. It was something new even to him, that had titillated and opened some new understanding of something, but I cannot presume to know what. His notes are unintelligible to me, and it leaves me powerless because he had spent the last year or more of his life figuring this out and it may now be lost.

Among David’s notes, boxes and boxes of them, was a study of Tuscan vernacular architecture—case coloniche, as they are called in Italian. Dad considered this form of architecture one of the most sensical and respectable building codes and modes every invented, and he set out to document it and explain it as a viable building mode. I knew he had worked on this because he went on a voyage through the Tuscan countryside after leaving my wedding, in Cetona, in 1998. I knew he had drawn several poderi, farm houses that were eloquent examples of vernacular architecture, because he returned to the States and made Christmas cards out of them and sent hem to people through the years. What I did not know was how many more there were, and how much more there was to his work on the subject—boxes of notes and observations which I hope to organize and publish for my father posthumously. His drawings of the poderi alone are, in Dad’s good fashion, spectacular, so I think he would appreciate it. After all it seems that the Tuscan podere ties together so much of Dad’s life and interests.

Of course, going through my father’s things includes remembering that my father, David, had had a childhood, too, and that childhood encompassed a great deal of learning about music and art—things I had heard about and learned about as a daughter of my father, but never as the adult who is now looking back on my father.

Going through Dad’s boxes I found his wonder spread in the arts of all kinds, beginning with his drawing and painting in his tweens, with Spanish painter Pierre Daura as mentor, and even earlier. He sketched animals, buildings, cabins, faces and trees with heart and skill. He was interested in light and structure and what made them work. By the time he was fourteen he had drawn the whole of my grandparents’ house and deconstructed it competently. By then Dad has also experimented with portraits and geometric constructions in painting, mostly under the guidance of Daura, for whom he also soon thereafter designed a cabin at Rockbridge Baths in Virginia, his first building, I believe.

Beyond the early love of drawing and understanding structure in building, Dad had loved and studied music. It was his first inspiration, music, reaching to the very core of his being. I have told in these pages what inspired him to play the violin from a very tender age—Smetana’s Die Moldau—and that led him to Eastman in spite of having lost hearing in one ear to a mastoid infection in childhood. I found boxes of his violin music, from Bach to Mozart, Handel, Brahms, Mendelssohn, Paganini, Beethoven, Hrimali, Schubert, and the Kreutzer Sonata, which, in his teenage years, he absconded to a faraway place to practice. Bob Garbee, a teenage friend of my father’s, told me of his devotion to music—how he could not be stolen away from it. He also told me that Dad offered to teach Bob how to sight-read music, a lesson he began with Brahms 4th Symphony, setting him up for immediate failure. My father had a clear cruel streak. As Bob Garbee told me, “Your father from an early age had little tolerance for human imperfection.”

Including his own. When he understood, at Eastman, that he would never be a good-enough violinist to be a concert performer, he left, without a kernel of self-pity. My mother told me, he knew that he could excel at something else, and he would never want to be lesser.

And I found among my father’s thing forty-something years of personal diaries, budget ledgers and journals written in tiny meticulous writing detailing the notable events of the day, factually and without sentiment, including such things as Sybil gets a lecture to I drank too much vino. Thing is, everything I looked at of my father’s, box after box of everything that was his life, was meticulous, careful, specific, precise, and thoughtful. His free-hand drawings are something that no so-called architect I know could remotely imitate.

During the course of the exploration of my father’s things it was hard for me to make sense of so much abundance and work and effort and care. My father wrote notes about everything—copious notations about the curvature of a cello back and the relationship to sound and color. The relationship between materials and harmony and structure. He was endlessly absorbed by Fibonacci and everything in nature that reflected on what he cared about—buildings, music, art. Everything to him had a larger connection and he looked at the world conscientiously absorbed by the inextricable connections between past and future, which included responsibility in building as well as teaching.

Since his death, I have come to learn that David—Professor Fix to others—was an excellent professor. He was kind, indulgent, compassionate, a good listener, concerned, inspirational, and rigorous (all of which I experienced as his daughter). He had a kind and generous disposition, colleagues say, and he was thoughtful and receptive to the needs of others and their views. He changed the lives of his students and made their minds better, as he did for me. One student told me that Dad often brought classical music to his classes so students could listen while drawing—and with him they had to draw by hand. Many commented on the richness of the conversations they had with Dad, insightful and humorous, too, encouraging them to look out of the box. One student recounted a drawing studio in which, regardless of the kind of project a student wished to entertain, the building had to contain a dumbwaiter so the residents or guests on the upper floors could receive their wine undisturbed.

It was that spirit, a mix of rigor and creative lightheartedness that I think led a student to feel comfortable enough to draw a caricature of him in class and present it to him. Dad cherished it, as do I.

My father characterized himself throughout his life as someone who could never finish anything. In self-deprecation he used to say that his life was littered by projects unfinished and imperfect, and that became part of his persona. I found a note that he titled ‘David’s epitaph’ chiding himself for having been born gifted and having done so little with it.

I chide you now, Dad, for having thought that.

My father was not an easy person to have as a father, or a spouse. He was demanding, acerbically critical, and sometimes cruel, and at times that narrow, plaintive familial narrative has obscured other light that was part of the man who was my father. It’s natural human error to view others through our narrative.

Now, through the passage of his death and the exploration of what he left behind—his things—I am coming to see and embrace who my father was outside of my perspective, separate from me, his daughter.

I am coming to a place where, finally, I can release the challenging story of living with Dad and embrace the story of coming from David. And that interests me, now, finally.

I am learning through this analysis of David Fix the man to let go of David the Dad, and though I will always cherish the moments my father gave me in holding my hand, or reading to me, or caring for my earaches, or teaching me how to ride a bike or how to make clay Christmas ornaments, his greatest gift was a mind and an inspirational, bottomless trove of wonder in all that surrounded him.

The vastity of David’s mind and its pursuits leaves me humbled and awed and inspired and heartbroken, too: the greater the pursuits and the gifts, and the greater the loss and sense of powerlessness. But it’s right just so, Dad: You sure never stopped traveling this thing that is life, taking your side trips along the way and casting about your insightful eye, and leaving me, along the way, many, many souvenirs to remember and understand you by.

I regret only that I didn’t spend more time with David the man rather than David the Dad. If only I had not been so caught in the trappings of daughterly expectations, of emotional disappointments—the things that father don’t do or don’t do right—I would have spent more time asking David about Fibonacci, and curves, and air through buildings, and so on, and about color and my paintings, and the violin concerto of Paganini, and the music of Brahms, who he so loved, and the story of how he accumulated dozens of signed concert programs from Carnegie Hall, and how, as a young man, he engaged in years of correspondence with famous musicians.

I would have spent more time asking why he thought what he thought about anything at all, because it would have been worth listening to, and that is a rare thing.

Now, in the man who was David I find my father, not the other way around.

Cheers, David, and thank you, Dad. I was lucky to be born of you.