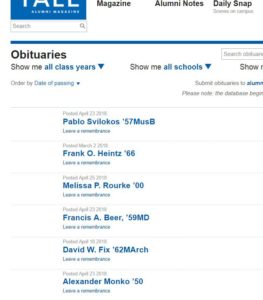

It burns my eyes to see it. It’s not that I didn’t expect it, and, in fact, I was even looking for it. I typed it myself and sent it in. I was wondering when it would run—when my father would be officially recorded among the dead, for all to see.

And yet, seeing it there in blue and white, his name on the list, the W. and all, it makes me flinch. It burns my eyes, that word, David, and that W. and the F, and the final x, which in his signature had a particular specific architectural proportion and flair and personality, distinct like his name and his life and he himself, deliberate and exacting and exact, never random or sloppy or careless, both in acts of beauty and of cruelty.

It burns my eyes to see it there like that, lifeless, like a name on a list is all that’s left, unmitigable and crushing, finite and final and finished and cut and dry, ungiving and unbending and ungenerous. Utterly non-negotiable is the W and the period, silent and still, now, no longer flowing from the glistening black ink of the fountain pen that he held between the fingers of his nice-looking hands, not large but not small, not fussy or manicured but elegant and clean and neat, strong but not overpowering. Hands of precision and meticulousness that drew beautiful and distinguished drawings with that same ink pen, and that carved violins that left shavings on the terracotta floor of his lab in our house with the French doors opening to the view of Monte Cetona and the land sprawling to Città della Pieve to the horizon. The hands that I remember at the source of that W. that stood for the maiden name of the woman from whom he sprung on this earth where he is suddenly no longer, with his hands and his ink pens and his violins and drawings.

All that is left is that name, the D, small and elegant with a tail, and the W with the perfectly positioned period. To look at his name in print makes me cover my eyes like a child seeing something bad and ugly, as if I could wish it away or run from it, his death, but there it is and it must be true, because it says so there, in black and white, with no space for the pinks and purples and greens that rest and dance in between: the whole world that my father was and is to me in both the poetic and the ugly and the singularly sublime that I will carry forever in me.

When I was a kid I often suffered from earaches. I was a strong child, and, later, an athletic, healthy kid, but I inherited the penchant for ear afflictions that, in his case, as a child in the early 1940s, left him, my father, deaf in one ear and almost dead. It was the loss of that hearing that prevented my father from becoming a concert violinist, the dream he had nurtured since he first heard the notes of Smetana’s Die Moldau as a child, at a concert with my grandmother. It was the loss of that hearing that crushed his dream and that eventually sent him, together with other things, into becoming an architect and a luthier. Anyway, that suffering, that excruciating physical pain that he had lived and that had left him scarred and defeated—and in fact I now realize that that pain had somehow defined his entire childhood and life in a way that I had never previously considered—had given him a particular empathy for the ravaging, maddening pain and life-altering danger that ear infections can inflict, and, so, when as a kid I had an earache, I experienced and saw the most tender, the most attentive and empathetic side of the man who was my father, and, in fact, an empathy that I never saw in him on any other occasion.

Even into my teens, at the onset of one of my earaches my father would lay me down on the couch in our living room with a blanket over me, and he would go into our little kitchen with the stove in the corner, with the glass door by the olive tree, and he’d put a shallow pan of water to heat, and he’d put the little dark-brown glass bottle of ear drops in the hot water to warm. Every few minutes he’d draw a drop to test on his hand like a mother tests the warmth of a bottle for a baby, and when they were just right—and with my father there was a ‘just right’ in everything, and particularly in this case because the stakes were so high—while tears of pain ran down my cheeks he would put the warm drops in my ears, one by one, tenderly massaging my ears to make sure the drops were properly absorbed to do their work and heal me. Then, with concern shadowing his tight brown eyes, he would retreat quietly to his lab and to his work carving and building, leaving me on the couch to fall asleep like a child swaddled in a blanket of safety, feeling protected and reassured as I never again felt at any point later in my life.

People say, I understand how you feel, and they want to share my mourning, the mourning of my father. And yet no one can. Death is entirely individual both in its claim of the life of the deceased and the claim of the living who stay behind to live on with their memories. My living of my father and with my father are mine alone, and entirely mine. For sure, no one felt the intense sense of love that I felt, singularly, in that tender gesture of care, and, to this day, when I revisit that memory I feel his love reaching into me.

Over the past several weeks since his death I have gone through a few of the famous passages or phases of mourning. On and off I navigate seas of anger—I have some beefs to pick and pick through—and regret, tons of regret, which, strangely, is not on the list and yet is my strongest feeling now. And then, too, enormous waves of tenderness and memory. Most recently, in the past two weeks, I have come to a pool of bottomless melancholy and sense of emptiness that I fear will never really entirely go away.

But, now that I think about it, staring at that W. as I am, and that D, and imagining my dad’s hand signing his name, maybe I am still grappling with denial, and refusal, too. And that may be why those letters and that name on that list in white and blue make my eyes burn so bad.