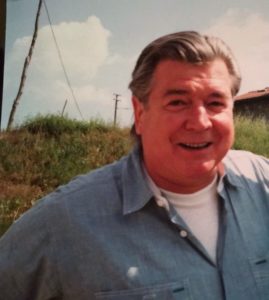

David W. Fix, violinmaker, architect, and professor, irreverent thinker and lover of ideas, and handsome man, died January 22, of cancer, in Eugene, Oregon. He was 85.

My father did not want a funeral or a memorial service, or even an obituary. A nonconformist and a non-belonger, he did not believe he had done anything worth commemorating. He was an atheist and a rationalist who believed that what we live and give and accomplish on this planet is all there is, and, mostly, little of it is of notice. He died saying that he had made the choices he wanted to make and that he had lived a good and full life.

What is certainly true to me, though, is that my father is a man worth remembering, and I am taking the liberty to defy him here on my blog.

David Fix was born October 4, 1932, in Erie, Pennsylvania, where my grandmother traveled to birth him in the department of obstetrics of which her father, a revered doctor who had chaperoned thousands of children into life, was chief. My grandparents lived in Lynchburg, Virginia, where my grandfather was a self-made and successful contractor, and that is where my father spent his childhood.

But, four fortuitous early and inspiring encounters with art and music chartered the path—primordial, for my father, I think—that he took as quickly as possible away from Lynchburg and the southern United States and its cultural and racial legacy:

The first happened when my grandmother woke him one morning and announced that that night they were going to the symphony. My father put forth his most persuasive arguments as to why he should not have to participate in this expedition, but ultimately my grandmother prevailed and off they went to hear Hans Kindler conduct the National Symphony Orchestra performing Smetana’s Die Moldau.

That night that music, otherworldly, swept him into an unknown and fantastical world, and in his childlike imagination he determined one day to be like those cats up there playing their violins, their bows breezily tracing arches through the air and making this heavenly music. He never forgot that night.

The second happened at the house of his friend Joe Cunningham, whose father was a successful and well-traveled geologist. When they played there—a house full of wonderful treasures—Dad, six or seven then, took books off the shelves and splayed them on the ground to look at the pictures. One of his favorite books was about the art and architecture of Rome, and one of Greece, and while he turned the pages he thought they were the most beautiful pictures he had ever seen.

—Mrs. Cunningham, are these places real?—he asked Joe’s mom one day when she came upstairs to check on them. —Do these places really exist?—

—Yes, David, they do, and one day, I am sure, you will see them.—

The third event that chartered Dad’s course happened when he took music lessons with Mrs. Graves. While waiting for the student ahead of him to finish, he sat looking at a wall full of art that entranced him. Among the small paintings and prints on the wall he saw an etching of a dancing character that he particularly liked. When Mrs. Graves came out of her lesson Dad asked her about it.

—Mrs. Graves, this is the most beautiful drawing I have ever seen. What is it?—

—It is a drawing by a man named Albrecht Dürer. Do you like it?—

—I love it, Mrs. Graves,—Dad said. —Can I have it?—

Mrs. Graves, moved by his precocious fondness for the drawing, promised he could have it when he finished his piano lesson book, and so it was. In spring she gave it to him, and he took it home like a most precious treasure.

The fourth came on the bus to school. My father, by then twelve or thirteen, was riding in the back when Pierre Daura got on. Pierre was a Spanish painter who had reached America during the Spanish Civil War and taught art at Randolph Macon College. Everyone in little Lynchburg knew who Daura was, and they talked about him. He was a man so interesting that all wanted to meet him, yet he was so foreign to the landscape, my father said, that even a child like himself noticed and knew.

Dad was immediately attracted to him and on the bus he approached him, introducing himself.

—Mr. Daura,—he said—my name is David and I have a Dürer drawing. My teacher gave it to me. Would you like to see it?—

—Do you, now?—Daura asked him, screwing up his eyes in disbelief.

Yes, my father said proudly. Daura gave him an appointment at his studio. Dad put his little Dürer in his knapsack, exactly as he had wanted to, and took it to him, and from there a lifelong friendship began. Daura taught my father to paint, the art that was my father’s greatest love.

Ultimately, during the course of his young life Dad studied music, played the violin, studied art and painted, and eventually, by a series of forces some beyond his control, he decided to become an architect—architecture being a practical art my grandfather endorsed.

Dad studied violin at the Eastman School of Music from 1952 to 1955. He served in the Army from 1955 to 1958, in Washington, DC, and eventually transferred to the University of Virginia to study architecture and graduated in 1959. He entered Yale Architecture School Class of 1962. The class had already been selected and sealed, but the dean and famous architect Paul Rudolph made an exception for my father on the basis of his drawings alone. He received his master’s, and his architecture licensing card was signed by no other than Paul Rudolph and Mies van der Rohe, by whom he was hired in Chicago 1962.

He worked for Mies until the icon died, then he started a small architectural firm with colleague and friend Phyllis Lambert. But ultimately my father became frustrated by an art—and a business—that perhaps never fit him entirely, though his sense of building and architecture itself, and the relationship between people and buildings, was instinctual and deeply felt, anthropologically rooted, deeply aesthetic, and denoting a keen appreciation for the supreme responsibility of building on this earth. Perhaps that was the crux—the responsibility of building on this earth.

All that became evident when my father decided to leave architecture to return to the source of his love—music—and to make violins, and we moved to Italy, when I was a little girl. Our home in Cetona was the reflection—simple, even primitively respectful—of a deep and diligent understanding of place and history. My father adored Cetona and his life there. It was idyllic and steeped in his greatest passions and interests, matured from those childhood days. And of course, in moving there my parents gave me what will always be my home, for which I am eternally grateful.

Dad attended the violin making school in Cremona and apprenticed under Master Luthier Francesco Bissolotti. He made instruments—violins, violas, and cellos—for nearly two decades and also embarked on a study, unfortunately never finished, of the properties of varnish and its impact on the quality of instruments.

He returned to the States in 1991, when the marriage of my parents ended, and he began teaching at the University of Miami School of Architecture, a position he held for nearly twenty years. He came to teaching late in his life, but he loved it and was devoted both to his students and the calling of teaching. Nearly every year, he taught in the Rome Program, on the architecture of that ancient city, of which he became a scholar. He treasured his times in Rome, soaking in and sharing with his students the love of architecture and art he so relished. He retired from UM in 2015, at the age of 83, and most recently lived in Eugene, Oregon.

Dad was always an idea traveler. Drawings and ideas occupied prominent places at our lunch and dinner table where Dad’s fantasies rolled out like little sparkling toys for me to follow, be it a portrait of a friend of mine or a drawing of a tree or a dome or an animal or a hemorrhoid, which often made for very funny times. We talked about everything—books, art, buildings, landscape, sex, man, mankind and its achievements and failures. He had no limits to his curiosity, intellectually. He pursued a study of case coloniche of Tuscany, for which he drew a series of exquisite live sketches, a study of a new design for a violin, and was in the process of writing an article on Mies van der Rohe when he left us, or, as he would have said, when he fell off his perch. He was a fascinating man.

Unsurprisingly, my father was not an easy man to live with. He could be temperamental, critical, and cutting as a Japanese sushi knife. He relished life and suffered it in a constant chafing struggle between ideals and limitations, the potential and beauty infinite and sublime and the limitations—for himself and projected on others—agonizing and crushing. Being in the world as a man was a difficult compromise in which children and wives and friends were often caught up. His universe offered a range of experiences from the stirring and the wondrous to the scalding and scarring, and sometimes the passage between the two unfolded in the blink of an eye.

Besides, my father was not a man of steely discipline, he did not serve the same employer for a lifetime, he was not involved in charities nor was he a man of the church. Really, he was not even a family man, and indeed, he was not cooperative, or often even nice, although he was very funny, very charming, and very nice, too. He was unapologetically his own person, iconoclastic, independent, and untraditional. He fails in all the revered obituary categories—and without remorse.

But my father was brilliant and exceptional in the depth of reflection and sensibility that churned inside him and that he took in from the world. He remembered minute details of people’s lives, and intricate details of conversations he had with people and the important things they had to say, even decades after the fact. Art, music, landscape, and human stories touched him deeply, and he shared that sensibility with me and everyone he thought would appreciate it. He loved food, and cooking, and dinner parties, and friends, and stories shared. I picture him tonight at a dinner table … or anywhere that was a source of beauty for him. Certainly one cannot say that he drove through life without looking: He looked and looked and looked, everywhere he went. He could spend weeks in a cathedral or a building he admired, or observing the rolls of the hills he loved, or a painting, and often when I was growing up I found him in the living room sitting alone listening to a Bach cello suite or a Brahms violin concerto, or a Dvořák concerto. In college the gifts he sent me were cassettes of that music he loved, carefully labeled in his unmistakable calligraphy, and drawings, too.

My father enveloped my world with a sense of independence and possibility in which I could do anything, a world where what mattered were ability, talents, and greater concerns. He cared nothing about appearances, false pretenses, status or money. He lived on his own terms, mostly unwaveringly. Often all that sorely lacked practicality, or sense of the common, but it made me who I am, a person enamored and engrossed with being part of a larger world of wondrous things that endure. And also living on her own terms.

All that I learned from the man who was my father, the man whose mind never ceased wondering and seeking and learning, up to the day of his death.

I will feel your absence, Dad, and miss you, for the rest of my life. I have no one to show my paintings to for feedback; no one who can as easily weave a fascinating conversation and know so much about so much; and no one to cheer me on when I embark on another idea that may not bear fruit but that comes from the deepest of my intuition. Though you starved my emotions sometimes and understood nothing of me in some ways, you appreciated and championed some things about me better than anyone else on the planet. In some ways you were my biggest fan, and for that I thank you.

Conversely, I am sure there is much I did not know about you, and, in fact, I regret if your life is not represented here to your liking. I am sorry for that. But I was most definitely your fan, too, and this is the best I know to do with what I do understand of you.

David was preceded in death by his brother, Bill. He is survived by his oldest son, my brother Paul, who lives in Italy; his youngest son, my brother Alex, in Eugene, Oregon; his second wife, Susan Fix, also in Eugene; my mom, Irene Fix, in Pennsylvania; and myself, in Charleston, SC.

With love forever.