I read recently about a family in a shelter in New York.

The parents had given birth to a child who had the saddest, saddest distinction of being born homeless, and so distinct it was that it was mentioned in the New York Times. This news of this baby filled me with dread, wondering what it, this status at birth, might mean for the baby’s life, for the future of the person he will become, or never become, future imperiled and today already laden.

I shudder still, because I cannot entirely understand. I have not reached that place. I do not know that station in life, and I hope never to.

And yet there was something in that story that I could understand.

In the interview, the father said that he and his family had become homeless when he had lost his job and they had lost their apartment. Before moving to the shelter, they had put all of their belongings in a storage unit, and they paid $200 a month to keep their things, what had they had left of their life before.

I am sure many or some among the rich readers—or even not so rich—sitting in their well-appointed apartments or houses thought that it was a superfluous expense, that of paying storage to keep one’s (we assume miserly) things while one is homeless.

And yet that father and I, he in a shelter in Manhattan and I in an apartment in Charleston, SC, have something in common: My things—all of them, every single one—also are in storage, in a metal unit twelve by twenty for which I pay $200 a month.

Immediately when I read the story I understood why it was important for that man and his wife to keep their things—the roots back to a stable life and, too, the memories of one.

It made me shudder in my borrowed bed in my borrowed (and lovely) apartment keeping homelessness at bay to think that our stuff could be something, a thread, to let us hope for a regular life once more.

I try not to think about my stuff much anymore. I used to think of my stuff a lot. Constantly. In the middle of the night it would wake me, crying, and during the day it would sway me away from my work. It would bring me sobbing to the floor, my stuff, curling up on the carpet. Its smell, the dust, the colors, the memory of lugging it around the world, comforting rather than heavy. All the memories within, and hope, too, of a life now suspended.

With a shrug people say to me, sell it all, let it go. ‘Who cares about stuff?’ On Facebook more than once I have been told what to do with my stuff.

But I inveigh against their thoughtlessness and ignorance, for my stuff matters, and it gives me joy to think of it all. Unlike a burdened donkey, it gives me wings to fly among the chapters of my life and unfold its pages, some otherwise dusty and unvisited, beginning, oh let’s see, with my wedding gown, satin pearl, with organza layering inside, hanging on a clothes rack barely beyond the portcullis.

I wore it, the gown, one apricot evening in July in the Tuscan hills from whence I come, and while the marriage ended, the memory of my princess-ness and the stability I thought it contained—and that precise light of the evening—still drags me back to wonder what exactly I was meant to do and why it did not work.

I kept the dress and hung it there when I returned to Italy for a year to write a book and ended up putting my stuff in storage, and so the thread goes backward, through my stuff, as I open the sliding metal doors onto all that I had and all that I seem unable (unwilling?) to redeem quite yet. Destiny speaking in metaphors, perhaps?

Just inside past the wedding gown and piles of boxes are the cow skulls from a cattle rancher in Montana. After I became a vegetarian and started painting animals and birds, I began a collection of skulls—bird heads and lizards to start—and I really wanted the skull of a big animal to revere and remind me of my place on the planet. I called a farmer in Montana who had advertised two skulls from long-horned highland cattle, one, he later told me, who had frozen to death in a long winter freeze, and the other killed by a predator, a wolf, he thought. We spoke on the phone about the long-haired, majestic animals for a few gracious hours, and he shipped them the following week in winter when the freeze let up and the FexEd guy could get through to his home.

I awaited the skulls and unpacked them with trepidation, and I have conserved those skulls as if they were human, or perhaps with greater care, for they were good animals and with humans you never really know.

There are etched silver plates from Athens in my storage unit, and some from the Greek islands with weather-beaten shores and merciless winds, bought on my honeymoon to faraway places full of treasures from centuries before anyone thought of this continent. There are rugs shipped and carried by me in duffel bags from Malta, with colors of pigments undreamed and undreamable, made by hands unshaken and poor in villages I will never know.

There are paintings from Istanbul, on parchment paper, from an artist I found in a store on a side street who flipped his stack of paintings like carpets and whose work, blessedly colored that blew my mind away, I wanted to buy all. There is a painting from Santorini, of the water-lapped houses on the harbor, painterly, detailed red and blue and turquoise, whose sight I took in while sitting in a bar—the kind of bar that makes you feel like never, ever, ever leaving—with my new husband listening to Loreena McKennitt whose stirring and melancholic voice awakened me to the fact that this would not last long, in spite of everything I wanted.

There is the painting of the goat—wistful? laughing?—that Mike and I bought at a pop-up gallery upstairs at Sermet’s Bar on King Street, before we were even married, the goat frisky, savvy, perhaps, or skeptical up on a hill, with a little white church in the background, painted by a young Asian artist, that we took home in the rain, under an umbrella, holding hands, and Wes Fredsell, the Charleston photographer, captured us on camera, unbeknownst to us, and published the photo in Charleston Magazine.

In a little box are all my Christmas things I wish I now had in my borrowed apartment, now, as Christmas approaches, and particularly the fragile clay ornaments my father made with my brother and me, several Christmases in a row, using the cookie cutters my Oma had used for butter cookies, and sugar cookies, too. Shaped like Christmas trees and reindeer and chickens and Santas, we cut the ornaments out of clay thinly rolled out on our marble dining room table in Cetona, and baked them and painted them by hand—some masterfully, my father’s—and glazed them to shine in the lights of the tree. They were so beautiful we shipped them in sets to relatives and friends everywhere and I remember one, a particular one, a sheep, painted by my father, that I long to see again.

In my storage unit I have stacks of photos I took of mosques in Turkey, many in Istanbul, but mostly of the stupefying Green Mosque of Mehmed I in Bursa, where I traveled across the mountains alone trying to find freedom and discovery and found myself on a bus of people who hated me because I had sat in the wrong seat and could not speak the language to make myself understood. In Bursa I ate stupendous food and was given overly enthusiastic massages by a Turkish man on the edge of a pool lined in marble turquoise and white. I learned to wash my feet at the entrance of mosques and to humble myself before the belief of others, and I spent hours there, humbled, so goddam lucky to be there, with the little glass lights suspended above me like lanterns from a lost dream I had never had the fortune of having.

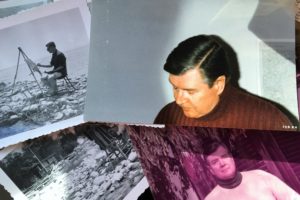

Stacked in the storage unit are little azure blown glasses from Mexico, each more exquisite than the other, and my collection of ceramic bowl made by Pippo, the ceramist in my hometown in Tuscany, and some of my father’s drawings, too, made in youth, when he was at the University of Virginia, of the Rotunda and Jefferson’s room.

Resting in storage silent and neglected are my many hundreds of books—Italian, French, and English, from all phases and passages of my life, from childhood to adulthood, bought and given to me, read by me and read by others, dogeared and ragged, new and old, gifted and regifted around the world—to which I used to turn for thought and recollections and words and memory, books that I have studied and leafed through and been given and many of which I have yet to read and which remind me of all that I want to learn and need to learn.

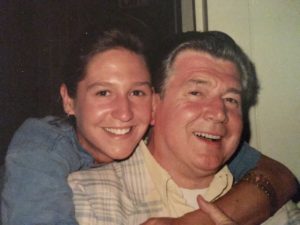

My father’s first violin is there—the first violin he made—and the first one he played, and all my furniture, some worthy, some not, and the chairs, original bentwood Thonet chairs given by my Auntie Phil, the heiress of the Bronfman fortune, to my father when they were partners in architecture in Chicago, when I was born. Auntie Phil took the first pictures when I was first born—also in storage, with every other photograph I own—and doted on me until we moved to Italy and she disappeared from my life. The chairs were shipped to Italy, then shipped back when my parents divorced, then given to me after my father died, and now they rest in my storage unit, looking, they too, for home once more.

In boxes somewhere with many, many paintings I care about, mine and of others, is the little etching of the joyful dancing man by Dürer, a treasure given to my father when he was a child and carefully kept through the decades, given to me at some point when I didn’t even understand its importance, to the point that Charleston painter Jill Hooper, visiting at some point, remarked how I should move it from the door, lest someone steal it. My father, just before dying, reminded me of the joy this etching gave him, and I cannot wait to see it again.

So beloved to me in storage are two dozen small beautiful ornamental mats from Afghanistan, intricately beaded, made by women in villages lost to the universe of the west, given to me over the course of some years by Mike after we separated. Every time he traveled to Afghanistan and returned alive, miraculously, he visited me bearing a few of these mats, something akin to doilies, because he knew I loved them. They remind me of the vastity of the universe to which we belong, the lives of women afar, the peoples I will never know, the landscapes I will never see, and I would choose them, those little mats, above all else in the case of a fire.

I have in storage rugs from Persia and Turkey, and rugs sent to me from Pakistan, and black and white pictures of children in Afghanistan atop dead tanks and cannons on barren landscapes. I have scythes from Cetona, from farmers I knew who used them to cut grass and wheat, and my Raggedy-Ann and my favorite doll, a black doll bought for me at Marshall Fields in Chicago as a goodbye gift before we left for Italy.

In a box, well wrapped, is my rice painting of a butterfly, from kindergarten in Chicago, which someone took the care to keep for me, perhaps in recognition of a first sign of something artistic in me, or perhaps a casual parental moment of affection. Little distant is a needle-point painting, of a delicate unicorn surrounded by a round fence, stitched by a friend of my parents on occasion of my birth. Bon-Bon Cooper, the wife of the architect Alex Cooper—she made that for me, to celebrate my birth into this world.

There is a collection of small hand-painted tiles from Sicily, and my collection of wooden cutting boards, scarred and carved out and concave and cut and breathing of faraway smells of herbs and foods, cutting boards marked and cut by the hands of women I knew and some I don’t. With it is my collection of wooden spoons, germinated from my mother and my Oma, steady Germanic cooks, and added onto at every occasion from the markets of Cetona to the many kitchens of women I love and grew up with, at whose tables I have eaten and whose food has inspired me. Their spoons are like their bones: to be kept forever and to be burned with me.

In my storage box are my first paintings, luminous and unguarded, innocent of the greedy and critical world I was about to enter, and my collection of bird houses: bird houses from France, in wooden sticks and metal bars, and copper bird houses from Charleston. I have a bird nest collection, wrapped and kept in bowls, and the flower press that Greta gave me as a child, with still inside the tremulous flowers I picked as a little girl.

There are framed photographs of the violins from the museum in Cremona, where my father learned to make violins, and in a little box somewhere is a set of delicate midnight-blue china horses, in glazed porcelain, given to me by my Zia when I was a kid. Once, when I was a teenager, I set out to dust them all, and when I sat on the bed to pay them greater care, they all piled up on top of each other, their ankles breaking as do live horses in races. I salvaged half of them, perhaps, and my father, who cared so much not about things but, now I understand, about treasures of our childhood given to us by people we love, he chastised me harshly.

I have among my treasures tealeaf tins from London, from our family friend Greta, a small manual sewing machine from Moscow that she brought back for me on the train across the tundra, and fossils of shells I found in our fields in Cetona, that amazed me when I found them and that still amaze me for demonstrating so clearly that what once were oceans are now mountains and fields, deposited through millions of years which make my stuff seem all really silly, in truth.

But then I also have dishes from my Oma’s kitchen, on which she, tall, with long fingers and a tender smile, served our family dinners—kartoffelkloessen, spaetzle, apfelkucken—on our visits to their home and on our rare returns to the States, when she was so happy to see us and already so sad to see us go, always self-denying the way she was, the salt missing, the food not enough, nothing she did ever good enough, like my mother and then myself. And I have her linens too, brilliant white and beautiful, the likes of which I will never be able to afford in case you recommend I throw them out.

There is, too, a set of old portraits painted by Aram, my lover of ten years when we broke up a few years ago, that he left in my storage unit while I was in Italy, as a gift before he moved to California. There is a quizzical man, and another still, puzzled, and a woman, too, all wondering what is happening to them. They are human and alive and they connect me to him every time I see them there, in storage, hidden and waiting.

And my wedding dishes are there, too, hand-painted in Deruta, a set of dozens and dozens bought by all my friends in Cetona, and a Revolutionary War medal won by a quadruple-great grandfather of my father who fought against the British somewhere in the South, the part of my family that I have been eager to deny and forget. I have a silver bowl given to me for my wedding by Annie, a friend now lost who could not understand my divorce, or forgive me for it, and linen towels from Antonella, embroidered by her with flowers, as a gift to me, and my many, many dish towels, collected from all over, which I love for their everyday company in the kitchen. There is my grandmother’s silver, on which my father’s family ate for decades, and candle sticks and silver bowls I brought back from Mexico, lush and shiny, and all my photographs—from childhood to wedding to graduations to every place I have been.

And there is also a half of a small onyx coin, with atop a painted woman, which I split with my friend Lucia as teenagers in Cetona, promising to be friends forever.

And so we are, thank god.

Just telling about all of these things that I have collected, kept, dusted, moved, packed and unpacked and moved again all so lovingly makes my heart glad, mostly because they represent and remind me of my love for people and places I have had in my life.

Indeed, they are reminders of layers of self and of moments of life and of feelings had and shared and of friendships and loves made and lost, layers of life exuberant and joyful and romantic and joyous. Things nothing short of joyous that contribute wonder and beauty to my surroundings—and unless you care nothing about your surroundings, those things matter.

Of course, all of those things have spaces carved in my memory, and my memory preserves them and their meaning, like people. Nonetheless, they themselves are not voiceless. Their presence itself speaks. They speak of where I have been and remind me of where I wish to go; of the beauty with which I wish my life to be surrounded; the books unread that I wish to read; the thoughts and history of people never seen in parts of the world I will never travel to. They fill me with wonder and curiosity and energy and beauty and mystery, small material manifestations of an interior world ineffable and uncontainable.

To some degree, being without my things has been strengthening. My life has become simpler. For four years I have slept on the same two sets of sheets, dried myself with the same handful of towels, eaten with the same two forks, cooked in the same few pans, all borrowed and not mine (and for which I am very grateful). All I have with me are a few dozen books I have purchased, my clothes, my art supplies, paintings I have painted in these past few years, and a few boxes of my father’s things, given to me after his death this year. I have little to dust or guard, and I feel free to think, uncluttered.

And yet—and I began to try to articulate this feeling when I read about the man and his family in the shelter in NY—being without my things now going on five years is in some way emptying, what I would describe as stripping of my identity and contributing to a haunting feeling of having lost myself somewhere along the way. It’s the feeling of my life having gone wrong and being less whole and stable and good. Which it is. Which I am.

In a way, not having my things destabilizes me, makes me lesser; takes away my belief in who I was and who I could be. It takes away my wholeness and deprives me of subtlety of being, my layers rolled into me silently and without footing. Even writing about it is hurtful and shameful. I wonder if I should say this at all.

I continue to hope—hope, our foolhardy crutch—that this will change, and I await the day when I will be in a place that is mine again, and when I can open my boxes and see my things again, and dust them and hold them and remember all that they mean to me.

And that, for me, will be Christmas again.